A Conversation with Sassafras De Bruyn about ‘Wesley and Wolf’ and Emotional Honesty

Share

Photo © Inge Kinnet

What was the initial spark or image that first brought the story to life in your mind?

The idea for ‘Wesley and Wolf’ (or ‘Wolf en Rolf’ in the original language, Dutch) started with one sentence. A play on sound that crept into my mind in the middle of one night: ‘There's a wolf inside Rolf’

The story and the message I wanted to give originated from that sentence. A reverse way of creating a metaphor, you could say.

I started thinking about this. Why would there be a wolf inside him? What could be the purpose? Suddenly, I felt two layers coming together: how that one sentence, seemingly floating on its own, applied perfectly to the struggle and mismatch I had been feeling for a while concerning emotional authenticity versus societal expectations.

The concept of the ‘wolf inside’ growing with hidden emotions is very powerful. Can you elaborate on the metaphor of the wolf and its significance in Wesley's journey?

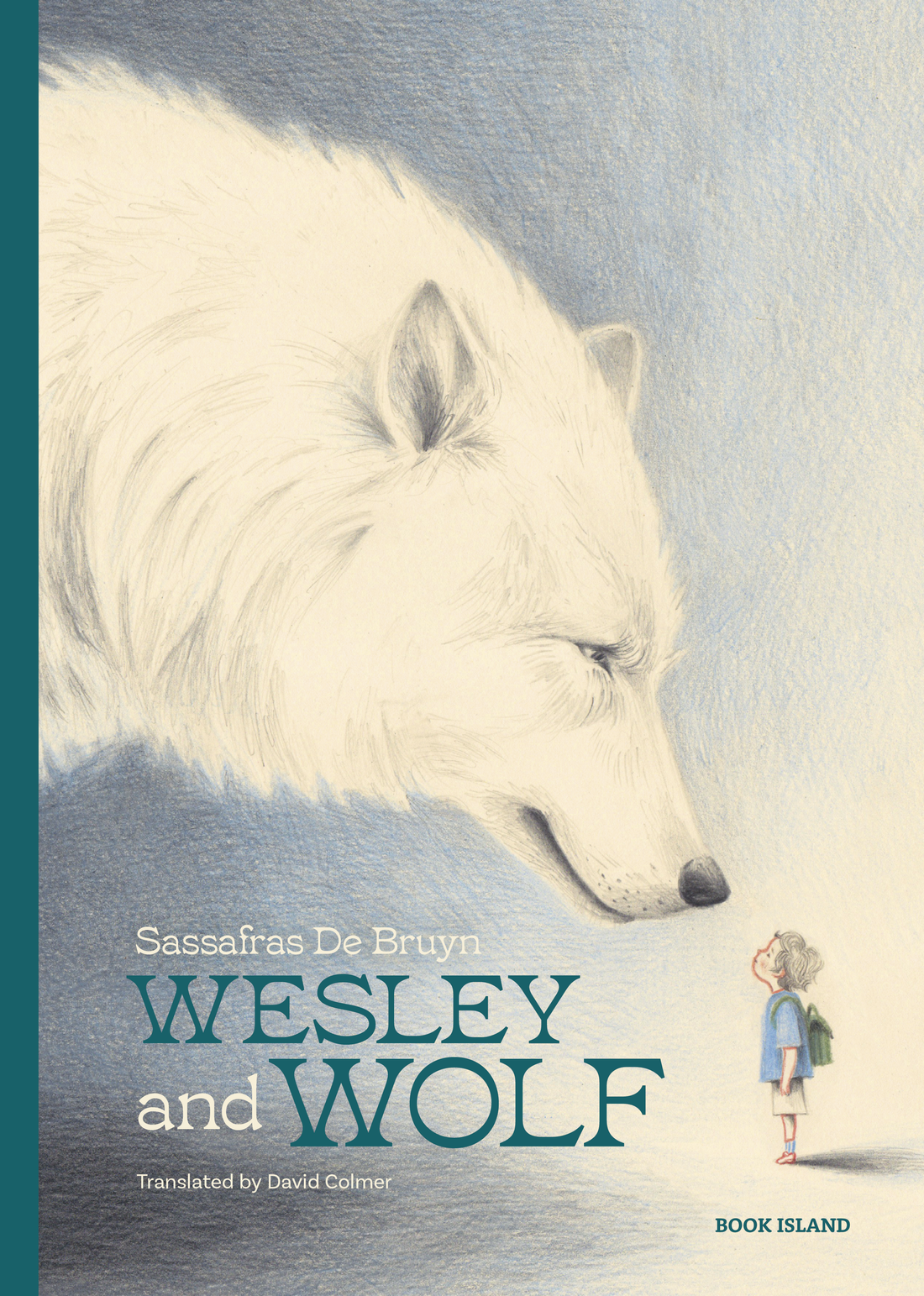

The wolf was the perfect animal to represent the wide range of normal - yet often negatively perceived - emotions that everyone deals with. Wolves are very often the villains in stories. They growl and show their teeth. But why should that always mean malice? Wolves show the whole range. They are also loyal and strong. They howl to communicate and are resourceful. In a lot of cultures, the wolf stands for intuition and inner strength.

In my book, I used the wolf’s wildness as an important beautiful characteristic. The Wolf inside Wesley growls, cries, laughs loudly and wobbles on his chair. He doesn’t suppress his so-called ugly emotions.

I used proportions to invigorate the message. When Wesley's feelings are very big and overwhelm him, Wolf is huge. Gradually, Wesley earns to feel and show what he feels, encouraged by Wolf. Wolf gets smaller, until he is only on the inside.

Were there any particular scenes or moments in the book that were especially fun or difficult to write?

I tell most of the story through the illustrations, especially the emotional development. I had a lot of fun with the facial expressions of both Wesley and Wolf. Especially when they were angry. The little boy in the car, for example, whose frustration is so enormous that the roof can barely hold the great wolf, crossing his arms and radiating fury.

Illustrating the bright red page where they both explode and yell ‘NO!’ felt cathartic, almost like I experienced the same build-up of emotions. I think I drew that one a lot quicker too, my hands moving faster and wilder over the paper. It was important that the pencil marks breathed the anger the characters were feeling, even more because Wesley finally expressed himself fully.

The very last scene, when the boy tenderly holds a tiny wolf in the palm of his hand, made me feel a lot as well. I made this drawing thinking of my own son, who was two at the time. I wanted him to always have that powerful reminder of his inner strength and intuition, like a lucky charm or a beautiful rock he would collect and put in his pocket, to grab when he would get insecure, overwhelmed or afraid to feel or show what’s going on inside him.

Are there any underlying themes or messages in ‘Wesley and Wolf’ that are particularly important to you, especially regarding emotional authenticity versus societal expectations?

I made a book about something that’s on my mind and in my heart daily.

Children are told a lot of things that cloud their intuition. It’s even more obvious now that I have children of my own. It breaks my heart to hear some of the things we tell our children.

‘Be brave, don't cry’, ‘Don't be angry’, ‘Give auntie a kiss’.... These may seem innocent things to say, but repeatedly told, they can lead to things like anxiety, burn-out, perfectionism, people pleasing… In those early years the impact of having to suppress everything can be vast and toxic, making us struggle as adults, with ourselves and with each other.

We create barriers to our own emotions by teaching our children to be good and nice and not too loud. Being allowed to feel what you are feeling is so incredibly important. When you are angry you are still beautiful, and good children cry too. You are allowed to feel the difficult feelings like anger, sadness and frustration, otherwise you’ll never learn how to deal with those feelings. You’re allowed to choose who you give a kiss or a hug and people should respect those boundaries. How else do you learn to set those boundaries when you get older?

What brings you the greatest satisfaction when creating books for young readers?

What gives me the most satisfaction is when children mirror things from books to their own lives and, in the process, discover something about themselves and the world around them that they may not yet had been able to put their finger on before. I love it when I see them think about something they read or saw, observe things, or ask questions. I am a firm believer that books are precious keys to open the doors of your mind from a very early age. Books stimulate empathy and emotional literacy and build much needed bridges between the self and the rest of the world. In our fast world of overstimulation, books bring these things in a slow way, with full attention.